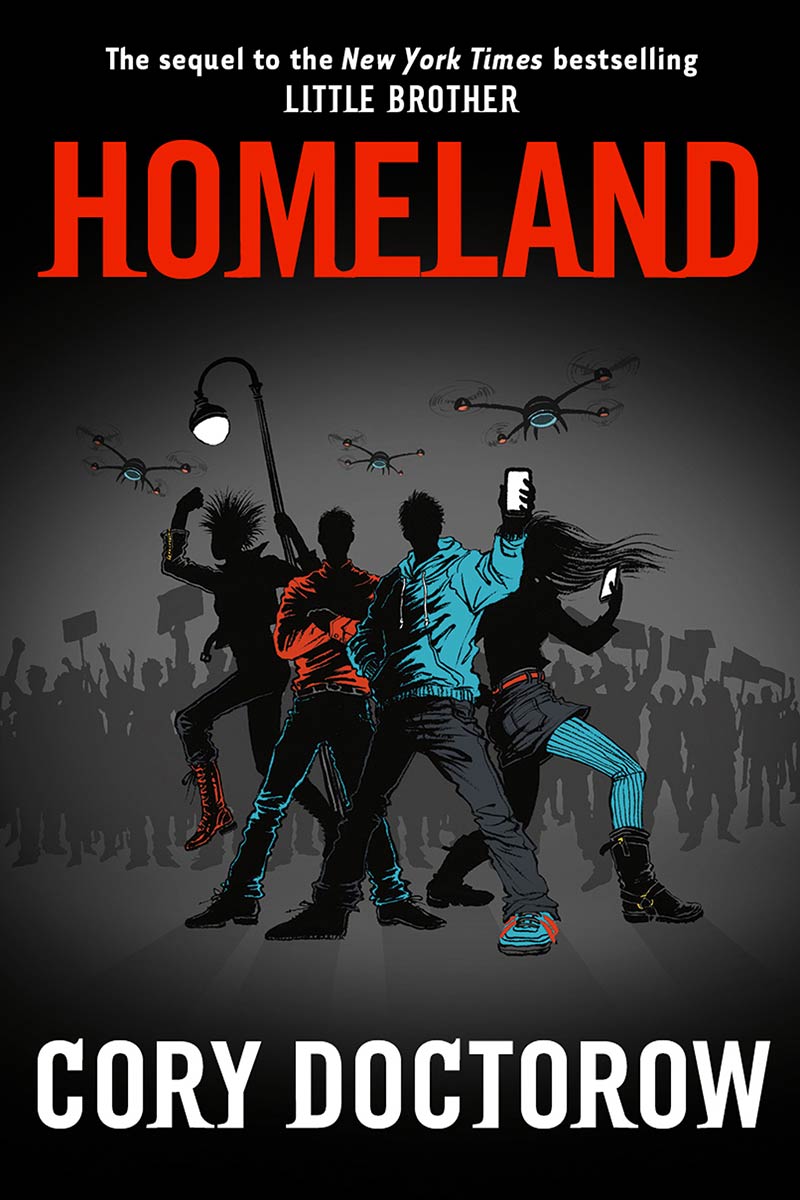

Jonathan Voß did me the kindness of adding hyperlinks to the afterword/bibliography for my 2013 novel Homeland. Thank you Jonathan!

When I was a kid, facts were hard to come by. If you wanted to know how to hack a pay phone, you’d have to find someone else who knew how to do it, and get them to teach you. Or you’d have to find operating manuals for pay phones and pore over them until you came up with your own method. There’s nothing wrong with either of these solutions, except that they’re slow and can be tedious.

Today, facts are cheap. As I type this in early 2012, a Google search for “How to hack a pay phone” gives back a full screen of detailed YouTube videos full of fascinating and often practical advice on getting pay phones to dance to your will. So if you know or suspect that a thing is possible, it’s easy to discover whether someone has managed it, and how they did it. Just bear in mind Arthur C. Clarke’s first law: “When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.” If you’re trying to do something that everyone on the net swears is impossible, it may still be worth a go on your own in case you think of something they’ve never imagined.

With Homeland — and in Little Brother — I’ve tried to give you some scenarios and keywords that might expand your impression of what is and isn’t possible, to give you the search terms you’ll need to educate yourself and get yourself doing cool stuff. So, for example, if you google “hackerspaces” you’ll find that places like Noisebridge are very real and have spread all over the world (Noisebridge is also real!). You can join your local hackerspace. If it doesn’t exist yet, you can start it. Just google “how do I start a hackerspace?” And while you’re searching, try “drone” and “tor project” and “lawful intercept.” You’ll be amazed, scared, energized, and empowered by what you find there.

Wikipedia is an amazing place to do research, but you have to know how to use it. Your teachers have probably told you that Wikipedia has no place in your education, and I’m sorry to say that I think that this is a lazy and dumb approach. There are two secrets to doing amazing research on Wikipedia:

- Check the sources, not the article.

In an ideal world, all the factual assertions in a Wikipedia article will have a citation to a source at the bottom of the article. Wikipedia hasn’t achieved this ideal state (yet — that’s what all those [citation needed] marks in the articles are about) but a surprising number of the facts in a Wikipedia article will have a corresponding source at the bottom. That ‘s where your research should take you when you’re reading an article. Wikipedia is where your research should start, not where it should end.

- Check the “Talk” link.

Every Wikipedia article has a “Talk” link that goes to a page where everyone who cares about the article discusses its state. If someone has a weird idea about a subject and finds a source somewhere on the net to support it, they might just stick it into the Wikipedia article. But chances are that this will spark a heated debate on the Talk page about whether the source is “reputable” and whether its facts belong in an encyclopedia.

Armed with the original sources and the informed discussion about whether those sources are good ones, you can use Wikipedia to get an amazing education.

Beyond Wikipedia, there are some other sites you should really have a look at if you want to learn more about the material in this book. First Codecademy , which contains step-by-step lessons to learn how to program, starting from no knowledge. You can even get them by email, one page at a time. While you’re chewing on that, check out the Tor Project and find out how to run your own darknet projects. If you’re looking to use an operating system that lets you control your whole computer, down to the bare metal, then you want GNU/Linux. I like the Ubuntu flavor best. It runs on any and every computer, and is really easy to get started with. And if you have an Android phone, get jailbreaking! The CyanogenMod project is a free/open version of the Android operating system, with all kinds of excellent features, including several that will help you protect your privacy.

Now, all this stuff is well and good, but only if the Internet stays free and open. If your country acquires the same awful censorship and surveillance used in China and Middle Eastern dictatorships, you won’t be able to get at this stuff and learn to use it. There are lots of threats to this freedom, and every country has groups devoted to stopping them. In the United States and Canada (and wordwide!) there’s the Electronic Frontier Foundation , where I used to work. In the UK, there’s the Open Rights Group , which I helped to found. In Australia, there’s Electronic Frontiers Australia . In New Zealand, there’s Creative Freedom . There are also global groups like Creative Commons and groups with lots of local affiliates like The Pirate Party .

There are lots of thinkers on this stuff whom I have a lot of respect for. If you want to know about teens, privacy, and networked communications, read danah boyd’s blog . For more on Anonymous, 4chan and /b/, read Gabriella Coleman’s blog and papers . For the future of news and newspapers, read Dan Gillmor , especially his excellent recent book, Mediactive . For the relationship of leaks to the news, follow Heather Brooke and read her history of Wikileaks, The Revolution Will Be Digitised . To understand how the net is changing the world, read Clay Shirky , and his latest book, the kick-ass { Here Comes Everybody }. If you want to fight for free and fair elections in America without undue influence from power and money, read Lawrence Lessig ( http://www.twitter.com/lessig ) and join Rootstrikers where activists are making it happen.

Finally, if you want to understand randomness, information theory, and the strange world at the center of mathematics, run, don’t walk, and get a copy of James Gleick’s 2011 book The Information . It’s where I got all the good stuff about Godel and Chaitin from.

There’s plenty more — more than would ever fit between the covers of a book, so much that you need the whole net for it. I write on a daily website called Boing Boing where I keep up to date on the latest stuff. I hope to see you there.