My new Locus column is What If People Were Sensors, Not Things to be Sensed?

more

All About:

News

My bestselling 2008 novel YA novel Little Brother has been optioned by Paramount, with Don Murphy (Natural Born Killers, Transformers) as the producer.

more

I’m doing a Q&A and signing at Reno’s Grassroots Books — a local, indie store with an emphasis on affordable reading for all — this Friday, Aug 28 at 6:30PM — just a quick stop on the way to That Thing in the Desert. I hope you’ll come by and say hello!

As the world’s governments exercise exciting new gag-order snooping warrants that companies can never, ever talk about, companies are trying out a variety of “Ulysses pacts” that automatically disclose secret spying orders, putting them out of business.

more

I did an interview (MP3) with the O’Reilly Radar podcast at the Solid conference last month; we talked about the Apollo 1201 project I’m doing with EFF.

more

My new Guardian column, What is missing from the kids’ internet? discusses three different approaches to teaching kids information literacy: firewall-based abstinence education; trust/relationship-based education, and a third way, which is the proven champion of the offline world.

That third way is making media for kids and grownups to use/enjoy/experience together. It’s what made the mission-driven Sesame Street so successful in its mission and the profit-driven Disneyland so profitable. We have some great media for grownups and kids to do beside one another (Scratch, Minecraft, Youtube), but nothing to do with each other.

more

Here’s the Q&A portion of the Cory Doctorow in Conversation event I did to benefit the Clarion West Writers’ Workshop in Seattle on July 28, 2015. The audio was provided Frank Catalano, who also conducted the interview. MP3

I’m teaching the Clarion West writing workshop in Seattle in late July, and you can come see me at two events, one on July 25, the other on July 28.

Postcyberpunk and Paella: An intimate evening with Cory Doctorow and Peter Biddle to benefit Clarion West. July 25, 2015 at 7 p.m.

Cory Doctorow in Conversation: Please join us for an evening of conversation with Cory Doctorow on July 28 at 7 p.m. at the University Temple United Methodist Church, 1415 Northeast 43rd Street, Seattle (across the street from the University Book Store).

Teaching Clarion West is a tough grind. I’m afraid that I won’t have time for any social calls on this trip — advance notice!

See you there!

My July 2015 Locus column, Skynet Ascendant, suggests that the enduring popularity of images of homicidal, humanity-hating AIs has more to do with our present-day politics than computer science.

As a class, science fiction writers imagine some huge slice of all possible futures, and then readers and publishers select from among these futures based on which ones chime with their anxieties and hopes. As a system, it works something like a Ouija board: we’ve all got our fingers on the planchette, and the futures that get retold and refeatured are the result of our collective ideomotor response.

Canada’s public institutions were very good to me today!

The CBC included Little Brother on its list of 100 Great YA Novels that make you proud to be Canadian.

Not to be outdone, the Toronto Public Library put the book on its Fight The Power: Books For Youth Activists.

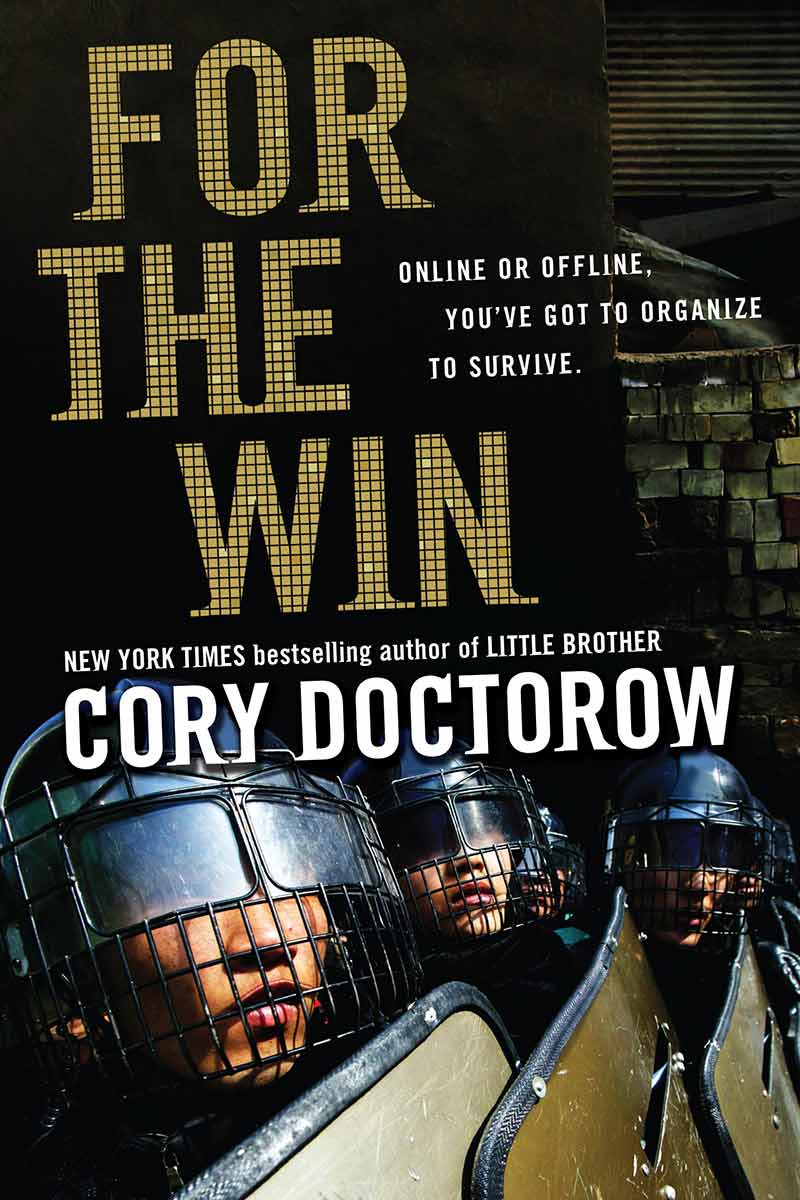

As if that wasn’t enough, TPL also put For the Win on its Boy Meets Boo list, featuring “Great books for guys: adventure, humour, fantasy and suspense.”