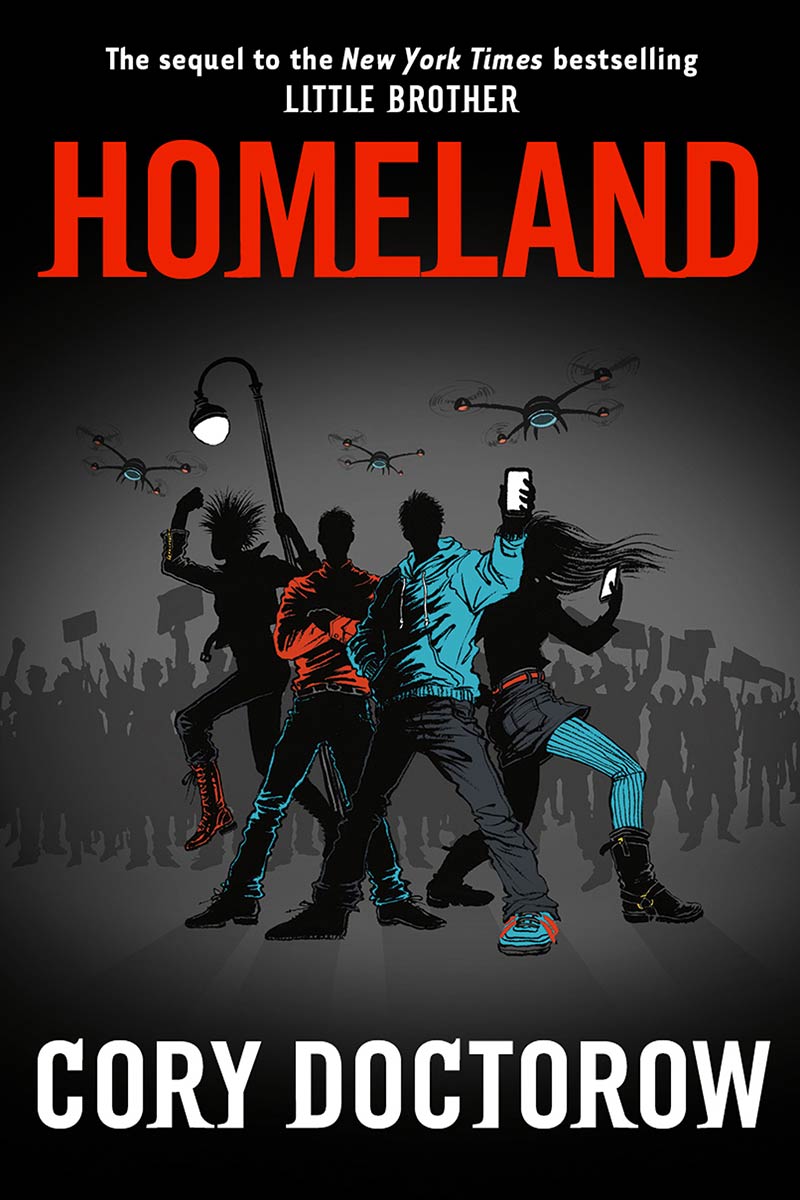

Homeland, the sequel to Little Brother, comes out on Feb 5, and as with my previous books, I’m going to be making it available as a free CC-licensed download. Whenever that happens, lots of people write to me to tell me how much they enjoyed it, and ask if they can just send me some money to say thanks.

I don’t want their money (don’t want to cut my publisher, who does so much to make the book happen, out of the loop), but I do want to help them share the love. So instead, I publish a list of librarians, teachers, and other people at similar institutions who would like free copies of my books, and ask people to express their gratitude by buying a copy of the book and sending it to one of them. It’s paying your debts forward in real-time. You do a good deed. The recipient gets to share my book with patrons, students, and other people who are looking to read it. My publisher gets the sale. The bookseller gets her margin. I get the royalty, and credit for the sales number (which improves my future advances, my position on the bestseller list, and my chances of making foreign translation sales). Win, win, win.

That’s where you come in. I want to launch the book’s website with a long list of people who want free copies of the book. If you’re a teacher, librarian, halfway house worker, shelter worker, etc, and you’re interested in getting your name on that list, please email my assistant Olga Nunes at freehomelandbook@gmail.com, and include your name, institutional affiliation, and its address and phone number (for shipping info). We’ll make sure it’s all ready to go when we launch.

Tell your friends! Spread the word!