The Random House audiobook edition of my novel Little Brother is a free MP3 download this week through Sync, a program that develops the audience of teen/YA audiobook listeners (it’s paired with Kafka’s The Trial, which is pretty cool). The file itself can only be downloaded with a proprietary downloader from Overdrive, which I couldn’t run under WINE on my GNU/Linux system, so I’m not sure how the process goes, but once you’ve actually gotten the file, it’s yours to keep for personal use as a plain-vanilla MP3 with no DRM.

All About:

News

The Random House audiobook edition of my novel Little Brother is a free MP3 download this week through Sync, a program that develops the audience of teen/YA audiobook listeners (it’s paired with Kafka’s The Trial, which is pretty cool). The file itself can only be downloaded with a proprietary downloader from Overdrive, which I couldn’t run under WINE on my GNU/Linux system, so I’m not sure how the process goes, but once you’ve actually gotten the file, it’s yours to keep for personal use as a plain-vanilla MP3 with no DRM.

MIT’s Technology Review is putting out an electronic science fiction anthology called TR:SF; I wrote a story for it about the future of “Internet of Things” called “The Brave Little Toaster” that was pretty fun. Other stories in the book will also focus on contemporary technology subjects.

My latest Guardian column, “Publishers and the internet: a changing role?” looks at how today it’s possible to “publish” a work without distributing it, without duplicating it, without doing any more than connecting a work with its audience, sometimes without knowledge (or permission) from the work’s creators:

In a world in which producing a work and getting it in front of an audience member was hard, the mere fact that a book was being offered for sale to you in a reputable venue was, in and of itself, an important piece of publishing process. When a book reached a store’s shelf, or a film reached a cinema’s screen, or a show made it into the cable distribution system, you knew that it had been deemed valuable enough to invest with substantial resources, not least a series of legal agreements and indemnifications between various parties in the value chain. The fact that you knew about a creative work was a vote in its favour. The fact that it was available to you was a vote in its favour.

Partly, this was the imprimatur of the creator and publisher and distributor and retailer, their reputation for selecting/producing works that you enjoy. But partly it was just the implicit understanding that no company would go to all the bother of putting the work in your path unless it was reasonably certain it would recoup. So “publishing” and “printing” and “distributing” all became loosely synonymous.

After all, it was impossible to imagine that a work might be distributed without being printed, and printing things without distributing them was the exclusive purview of sad “self-publishers” who got conned by “vanity presses” into stumping up for thousands of copies of their memoirs, which would then moulder in their basements forever. But just as the internal functions of publishing were separated out at the tail of the last century, this century has seen a separation of selection, duplication, preparation and distribution. Every work on the internet can be “distributed” by being located via a search-engine without ever being selected or duplicated or prepared.

Make Magazine’s just reprinted my column, “Moral Suasion,” in its online edition. It’s a discussion of the politics of cloud computing, including denial-of-service attacks against cloud providers who cave to government pressure:

I grew up in the antiwar movement and participated in my first sit-in when I was 12. Sit-ins are a sort of denial of service, but that’s not why they work. What they do is convey the message: “I am willing to put myself in harm’s way for my beliefs. I am willing to risk arrest and jail. This matters.” This may not be convincing for people who strongly disagree with you, but it makes an impression on people who haven’t been paying attention. Discovering that your neighbors are willing to be harmed, arrested, imprisoned, or even killed for their beliefs is a striking thing.And that’s a crucial difference between a DDoS and a sit-in: participants in a sit-in expect to get arrested. Participants in a DDoS do everything they can to avoid getting caught. If you want to draw a metaphor, DDoSers are like the animal rights activists who fill a lab’s locks with super glue. This is effective at shutting down your opponent for a good while, but it’s a lot less likely to draw sympathy from the public, who can dismiss it as vandalism.

(Image: Sit-in “Giornata degli studenti”, a Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (2.0) image from retestudentimassa’s photostream)

Anastasia Salter gave a presentation on my novel For the Win at the Children’s Literature 2011 conference; I haven’t seen the presentation, but her notes (embedded above) are fascinating!

Anastasia Salter gave a presentation on my novel For the Win at the Children’s Literature 2011 conference; I haven’t seen the presentation, but her notes (embedded above) are fascinating!

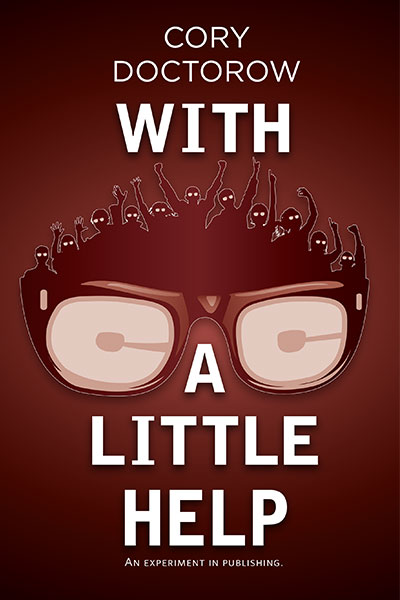

Last week, New York’s McNally-Jackson Books started printing and carrying my DIY short story collection, With a Little Help using their on-site print-on-demand machine. Now, the most excellent Harvard Bookstore has begun to do the same, retailing the book in its Cambridge, Mass store.

Last week, New York’s McNally-Jackson Books started printing and carrying my DIY short story collection, With a Little Help using their on-site print-on-demand machine. Now, the most excellent Harvard Bookstore has begun to do the same, retailing the book in its Cambridge, Mass store.

My latest Guardian column, “Networks are not always revolutionary,” argues that networks are necessary, but not sufficient, for many disruptive commercial, cultural and social phenomena, and that this character has led many people to either overstate or dismiss the role and potential of networked technology in current events:

“For most artists,” as the famous Tim O’Reilly aphorism has it “the problem isn’t piracy, it’s obscurity.” To me, this is inarguably true and self-evident – the staying power of this nugget has more to do with its admirable brevity and clarity than its novelty.

And yet, there are many who believe that O’Reilly is mistaken: they point to artists who are well-known, but who still have problems. There are YouTube video-creators who’ve racked up millions of views; bloggers with millions of readers, visual artists whose work has been appropriated and spread all around the world, such as the photographer Noam Galai, whose screaming self-portrait has found its way into everything from stencil graffiti to corporate logos, all without permission or payment. These artists, say the sceptics, have overcome obscurity, and yet they have yet to find a way to convert their fame to income.

But O’Reilly doesn’t say, “Attain fame and you will attain fortune” – he merely says that for most artists, fame itself is out of their grasp.