William Gibson Interview Transcipt

Penguin/Putnam offices, Toronto, Tuesday, November 23, 1999

Cory Doctorow

|

This is the raw transcript of the interview I did for the

William Gibson story I did for the

Globe and Mail. I wish I'd had more room to insert

Gibson's quips in the story, but they limited me to 1600 words.

Gibson never meets your eye when he talks to you. I'd been warned about this going in, but otherwise, it might've inspired quite a fit of self-doubt. In person, he's really tall, and very affable, with an easy smile. I had invaluable assistance with this interview. First of all, the people at Bakka referred the Arts Editor of the Globe to me. Then I got a wonderful briefing on Gibson's hot-buttons from Sean Stewart and Mark Askwith, who'd interviewed Gibson a few times for Space: The Imagination Station and TVOntario's Prisoners of Gravity. Finally, Dave Nickle, who's an actual, working journalist as well as being a hell of a fiction and nonfiction writer worked with me on interviewing strategies and copy revisions. Thanks, guys. |

|

Download this article as a Pilot-readable document |

(it's 8:30 in the morning)

CD: I think "All Tomorrow's Parties" is the most character driven novel you've done to date. You seem to be making a nod to this in the text itself, when Rydell considers the Zen assassin's violence and attempts to reconcile the romantic ideal of violence he's pursued and compares it with the banal horror of real-life bloodshed. You've written pretty romantic violence yourself -- the fight in Johnny Mnemonic comes to mind. Is this a repudiation of romantic bloodshed?

WG: I'm owning romantic violence, as they say these days. I'm owning Rydell's awareness of its banality. I probably had something to do with being southern. For some reason, over the last few years I've been much more conscious of that. It's probably because my friend Jack Womack has a thesis that he and I write the way we do because we're southern and we experienced the very tail end of the premeditated south. In effect, we grew up in a sort of timewarp, a place where times are scrambled up. There are elements of my childhood that look to me now, in memory more like the 1940s or the 1950s than the 1960s. Jack says that that made us science fiction writers, because we grew up experiencing a kind of time travel. A part of that for me was growing up in a culture that violence had always been a part of. It wasn't an aberration, though I realise that in retrospect. I grew up in the part of the U.S. where all of Cormac McCarthy's novels are set and that's a pretty violent place. There's violence in my culture. It's an American thing, but it's particularly a southern thing, and its romanticization is hyper-Southern. And it's still irresistible to me, even in middle age. There's something that pulls me to that, but at the same time, I have this increasing awareness of how banal it really is -- that evil is inherently banal.

I loved the Limey! It's so violent! And yet it's so exquisitely romanticised in a sort of Japanese way, it's a samurai film. Coming out of that, I was really deeply conflicted, because a friend who had seen it said, it's beautiful, but it's not about anything. it's one micron thick.

Yeah, it's true, but that southern romantic part of me just schwoom, I was right there, really quite worked up. It's a strange thing, anyway I'm rambling... (laughs)

CD: Interstitial Zones hold another kind of romance for you. But real-life Interstitial Zones are often as banal as the wost kind of violence: think of the terror in the former Soviet Union, or the rape and riots at Woodstock '99.

WG: Well, to some extent I'm guilty of wishful thinking. The absence of the interstitial I find unbearable. But not as unbearable as the idea that interstitial is necessarily as banal as the infrastructure, so I think of what I do with that stuff as a glorification of possibility. And very probably at the cost of naturalism but to go in the other direction would be to despair.

I think that one of the visions that is closest to reality is the cardboard city in the subway station in Tokyo, which is based very closely on a series of documentary photographs of people living like that and of the contents of the boxes. Those are quite haunting because Tokyo homeless people reiterate the whole nature of living in Tokyo in these cardboard boxes, they're only slightly smaller than Tokyo apartments, and they have almost as many consumer goods. It's a nightmare of boxes within boxes.

To the extent that I can still believe in Bohemia, which I think is very important to me in some way that I don't yet really understand, to the extent that I still believe in that, I have to believe that there are viable degrees of freedom inherent if not realised in interstitial areas.

CD: You used to live in Toronto. What's your thinking on it these days?

WG: What strikes me about Toronto, and it's been very strong on this visit, is that Toronto's great misfortune was to have too much money in the late 70s and early 80s, and consequently, it built in the style of those periods, which is hideous... It's as though the city were being forced, forever, to wear very wide ties. A lot of the buildings around Yonge and Bloor is the architectural equivalent of Kipper Ties and 8" collar points. It's ghastly and no amount of street-level retail glitz can lift it.

But then I look at it and think well, perhaps my grandchildren will someday look at this stuff with the sort of appreciation I once held for Art Deco. Although I've come to find Art Deco quite creepy too. (laughs)

Art Deco just doesn't do it for me except in its most crazed and attenuated forms, it's jut a matter of taste. Somehow I think that if Toronto had been forced to wait a decade, it would be a better looking city.

When I come to a new city is I combine: I say, well, it's like Barcelona and Edinburgh, though I can't imagine what that would be. But Toronto, the last few times I've been here, what always comes up is Chicago and West Berlin. It's a big, sprawling city beside a lake, of a certain age and a certain architectural complexity. But the high-end retail core looks more like West Germany than the Magnificent Mile. Yonge Street is like K-Damm. There's an excess of surface marble and bronze: it's Germanic and as pretentious as pretentious can be.

CD: A strong vein of nostalgic appreciation of artefacts runs through all of your work: from the Gernsback Contiuum to assemblages pieced together by the AI in the Neuromancer trilogy to the watches and Skinner's jacket in the latest series. Your autodestructing poem Agrippa is an especially poignant piece of nostalgia expressed in artefacts. And you're not the only one: eBay and the Antiques Road Show indicate a growing worldwide passion for collectibles. Is this being fuelled by the digital revolution and its intangible productions? Will we ever get weepy about outmoded software for computers that don't exist any longer?

WG: I'm sure we're generating ephemera, hard consumer goods ephemera, but the ephemera of one's own day is invisible. You can't really see it.

I think that the collectible ephemera craze/awareness is probably driven by a reverse market, rebounding off the sense of everything being mass-produced. It's the last step you take in trying to find something unique.

Every shop in every High Street in Europe is filled with basically the same stuff. There's a street in every city of the world that has a Gap and Benneton's, and the upscale versions of those.

For me, the melancholy of the late XXth Century is walking late at night by the Mont Blanc pen store and seeing these things always strike me as simulacra of luxury items. They seem like fakes: you know that they're on every High Street on the planet, so a 1925 Mont Blanc pen of a particular provenance becomes the real luxury items.

That doesn't explain the obsessive investment in Beanie Babies. That doesn't explain Barbie dolls. I was once really close to sitting down and having a conversation with a shadowy young woman who is reputed have become a millionaire by investing in Beanie Babies. She was someone that a couple people claimed to know, she seemed to exist, but she remained shadowy.

CD: Your work is heavily international in its scope, but while other writers have chosen to focus on Mexico (as Sterling did in Heavy Weather), or Russia (like Womack in Let's Put the Future Behind Us), you've stuck to the west coast and to Japan. What's the fascination with Japan? How is it connected to the west coast?

WG: When did it become necessary to explain what's so cool about Japan? Everyone was quite obsessed with it 15 years ago. Have we gotten used to them? I find them more interesting in their post-Bubble state than I did when they were the centre of the world. I suppose it's the only Asian country that developed an imaginary entree to me. That's why I go back.

I suppose I do the Japanese because I just don't know China. Chinese popular culture has never evoked that instant of, "Whoah! What's that?" that I have with Japanese popular culture.

I'm not the only one: witness Pokemon! They still keep coming up with this stuff that just rivets us in unexpected areas. Was the fact that Pokemon anime gave Japanese schoolchildren epileptic seizures part of the phenomenon? Was it planned?

I've been hearing things about what Tokyo is like. I only go to Japan when there's someone who can afford to bring me there, and consequently I may never go again! It's been a while since they had the discretionary capital. But I have friends who go there frequently on business, and it sounds interesting. I've heard that they have for the first time serious drug problems.

CD: In your commencement speech to Jim Blaylock's son's class, you talked about the disassociation between Gibson-the-writer and Gibson-the-person. "All Tomorrow's Parties" is your most humanist novel; you can see this in how the scene changes are announced by turning points in the characters' internal monologue, rather than in the plot. Is the barrier between Gibson/writer and Gibson/person coming down? How do you reconcile the hard, Hammett-inspired fiction you began your career writing with humanism?

WG: For me, it's just experimental, it's process rather than result. I'm only able to get a handle on what I've been doing -- in terms of my whole life, but particularly in terms of my writing -- I can only do it in retrospect. Moving forward in the process, if someone comes in and says, "What are you doing," if I'm honest, the answer is, "I don't know. But I'm doing THIS, don't know why." (laughs)

I've observed what you're describing [the integration of Gibson-the-person with Gibson-the-writer] in the process of writing the book, and my reaction to it was to scratch my head and say, "What's that?"

The construct of William Gibson the Writer is coming down, and become more open. It's more of a Glasnost -- Transparency! Transparency is what it is.

I think that I've always written about things that are very personal, but initially, I coded everything. I buried everything under layers and layers and layers of code, but the signifiers of my emotionality were there, for me. I knew where the magnets were, behind the gyprock, and the magnets were very powerful. I think they had to be powerful for me, otherwise the reader wouldn't have a reciprocal experience. But I was very careful to bury them deeply, deeply in the plaster and paint over them. I didn't want anybody to directly access them, and that's gradually changed for me.

I don't know if it's writing about the near future that's brought that out, or whether if its' the emergence of that that's caused me to write about the near future.

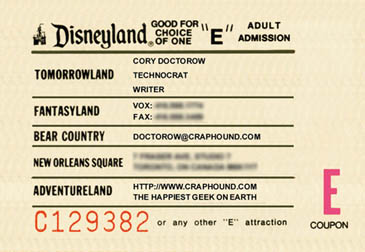

Gibson laughs at my business card |

My business card |

CD: Rez is a celebrity who makes a nearly disatrous attempt at re-branding himself as a virtual person. Gibson-the-writer is a household name -- in marketspeak, you've become a brand. This was especially evident in the dustup over Autodesk's attempt at trademarking "cyberspace" and your counterstrike trademarking of "Eric Gullichsen." In the eBay world, we're all retailers, dutifully building our feedback level -- our brand-identity -- to make ourselves better retailers. Your work is full of brand-names: are you making a point about branding?

WG: The experience of celebrity is gradually being democratised. Maybe I've been a small part of the democratisation of celebrity, because I've been fascinated by it, and when it started to happen to me to the very limited extent that it happens to writers in North America, I was exposed to people who had the disease of celebrity. People who had raging, raging, life-threatening celebrity, people who would be in danger if they were left alone on the street without their minders. It's a great anthropological privilege to be there.

It seems as though everyone is going to the currency of celebrity. Everyone's getting their own account of whatever that currency is. That's something neat. It used to be only the elect had any manna in the information society and everyone else was a consumer.

I think I knew that it started Johnny Mnemonic was coming out and I realised that all the kids that worked in 7-11 knew more -- or thought they knew more -- about feature film production than I did. And that was from reading Premiere, that was from this change that came from magazines that treat their readers as players. Magazines that purport to sell you the inside experience.

I realised that everyone in Western society, in some weird way, believes that they've had the experience of producing feature films. You can get in a cab in Vancouver and the 20-year-old driver speaks more knowingly of Michael Ovitz than anyone in the industry. They just know! And it's perhaps not unhealthy.

Although my own experience in that arena has left me convinced that the actual experience of being there remains esoteric, and that people who live there have a very powerful interest in maintaining the exclusivity of the real area.

There's always a real area. A couple of times I've gone to big stadium rock concerts at some artist's invitation, and there's this invariable, fascinating and rather sad situation of concentric circles of availability. There are Green Rooms within Green Rooms literally within Green Rooms. There are seven or eight degrees of exclusivity, and within each circle of exclusivity, everyone is so happy to be there, and they don't know that the next level exists. It's like Freemasonry, and eventually you find yourself in the room with the Radiant Being around whom all this is revolving. It's very bizarre, and it's quasi-religious, or possibly genuinely religious. Spooky. It's a spooky and interesting thing.

I'm always aware of being aware of being in the presence, not of the star, but of an incredibly important phenomenon: some mammal ritual that is being acted out by thousands of people, who come together in one place. It's Hitlerian.

CD: You began your career heavily influenced by counterculture: writers like Chip Delany and artists like Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. These days, counterculture is just another brand, co-opted faster than the street can create it; you might even say "Madison Avenue Finds its Own Uses for Things."

WG: I worry about what we'll do in the future, [about the instantaneous co-opting of pop culture]. Where is our new stuff going to come from? What we're doing pop culturally is like burning the rain forest. The biodiversity of pop culture is really, really in danger. I didn't see it coming until a few years ago, but looking back it's very apparent.

I watch a sort of primitive form of the recommodification machine around my friends and myself in sixties, and it took about two years for this clumsy mechanism to get and try to sell us The Monkees.

In 1977, it took about eight months for a slightly faster more refined mechanism to put punk in the window of Holt Renfrew. It's gotten faster ever since. The scene in Seattle that Nirvana came from: as soon as it had a label, it was on the runways of Paris.

There's no grace period, so that's a way in which I see us losing the interstitial.

CD: You grew up reading Delany; Neal Stephenson grew up reading you, and at the same time, he's an accomplished programmer, who arguably gets the technology details better than you. Is your audience his audience?

WG: I've always assumed from the beginning that I had relatively few contemporaries among my readership. Not that I was consciously writing for a younger audience but that what I was doing interested a younger audience, or at least threatened them less. The people my own age who came along and were enthusiastic tended to be chancers of one sort of another. The broader audience were younger people who were less invested in the status quo.

When Neal Stephenson came along, I assumed on the basis of Snow Crash that he would find a big part of his audience among my audience. There's a natural overlap.

But I don't know who comes after Neal Stephenson. In England they think they do, but I still haven't read Ken MacLeod and Greg Egan, but they're very well-thought-of.

I'm going through a period where I can only read Ian Sinclair, it's all I can read.

At this point I've reread -- often randomly -- Lights Out for the Territory about five times in the last year, though I don't really know why. There's something there for me; it's like working some kind of palimpsest. There's something really important that book is trying to tell me that I haven't really realised.

CD: There's a lot of talk in Canada these days about brain-drain as the brightest leave for the US and its lower marginal tax-rate. You could certainly benefit from such a move, and since you were born in the US, it should be relatively easy to accomplish. What's kept you in Canada?

WG: I like living in Vancouver (laughs). It's more a matter of being a Vancouver loyalist. Harking back to what I said about growing up with the inherent violence in the southern U.S., I'm deeply enamoured of, and entirely used to living in a society with gun laws akin to those of a Scandinavian social democracy (laughs). It's a good thing.

I like the Canadian program. When I came here, when I was getting used to the country in the 70s, it all made sense to me. To the very limited extent that I have a political consciousness, to some extent I'm a lazy, apolitical sort of guy that just flits around.

If I were going to leave Vancouver, if I had to pick a place to go, it would probably be London, which has WORSE taxes, and more expensive real-estate, but where I feel, in some ways, more at home. I don't know where I'd go in the U.S.. I get to travel there very widely, and that may be part of it: by virtue of doing these book tours every few years, I get the cook's tour of the whole country. I almost never see anywhere where I can imagine wanting to stay: New York, Los Angeles, and that's it (laughs). It's narrowed down to that, which shocks me, because I didn't think I'd become one of those people, the flyover people.

If I were in severely straitened socio-economic circumstances and had to move to the U.S., I'd probably opt for Athens, GA, or Lawrence, KS. As boho guys usually do, live cheap in the Left Bank of Kansas.

CD: There's been a mergers-and-acquisition mania in New York publishing lately, and a lot of midlist writers have written about the death of the midlist. You don't hear a lot from best-selling writers, though: do you have any thoughts on the subject?

WG: [The death of the midlist] concerns me and I don't understand it. Career publishers I know and trust have no idea what's going on, why it's happening, what's driving it. Publishing is not a comfortable place to be.

You know, it's funny, for decades people have been coming to me and saying, "Whoah, Cyberspace! What's the future of the book, that sacred object?" I've been through the whole western world, and it seems to me that there's more retail floorspace devoted to the sale of books than food! There's more retail floorspace devoted to the sale of books than there's been in the entire history of humanity! It's grotesque! (laughs) The Simpson's in Piccadilly has been turned into the largest bookstore in all of Europe! How can they fill it? All of these purpose-built Borders and Chapters and every new mall that goes up has a giant chain bookstore with a purpose-built author reading space, whoah, what's gong on there.

I find it scary -- I'm very primitive in terms of economics, ignorant, really -- the hunch it gives me in my ignorance is that the strength of the chains lies in growth. The kind of new business in which stock gets more valuable because the company grows, but there must be limits to growth. But if publishing is expanding to fill that retail space, it seems like there may be a necessary and unpleasant correction waiting down the road. How many books to people WANT?

CD: The computer age is the age of the nerd. How does it feel to be a member of the last generation of nerds that failed to inherit the earth?

WG: My expectations in terms of inheriting the earth were astonishing low, twenty years ago. I still suffer to a certain degree from Impostor Syndrome: is this my beautiful house? I feel like I've been very fortunate in that I've stuck like a burr to the dog-leg of the next generation of nerdism. I've been carried into the XXIth century on Bill Gates' pants-cuff.

CD: Sterling says I need to ask you about shoes: what about shoes?

WG: I was travelling with Bruce Sterling on our mutual Difference Engine tour and he became aware from the experience of travelling with me that I would distinguish among the shoes in a perfectly normal fashion, but form him it was a revelation. There's a very lyrical passage in Holy Fire about old wealthy European men and their shoes, and how beautiful their shoes are, and how there have never been shoes as beautiful. I think that that was probably as close as Bruce will ever get to homage in my direction. I made him aware of footwear fashion.

CD: Finally, I have to ask: tell me about your watch.

WG: This is a 1949 Jaeger Chronometer with a stainless steel case and a hand-painted original silver case, which I got on eBay. This is my free Wired watch, from doing the Wired article. If I had more time, I'd take it to this famous watch-otaku here in Toronto and get him to tell me what it's worth. I want to keep it, but that's part of the hoarding pleasure.